The world of journalism is changing fast. Reporters over the last ten years have been thrown into a rather intimidating world pool of social media and networking developments, faced with the prospect of keeping up with the times or else risking their careers. Lightning fast internet connections combined with far reaching influence of internationally integrated social networks has made information gathering and processing more comprehensive- and trickier- than ever. Social media has indeed changed the very essence of the news, from what is reported and how, to what professional journalists do differently, and how this all affects public perceptions and preferences concerning the news.

To fully understand the impact social media is having on the life cycle of news, we must look at what news gets reported and gains traction, how reporters act, and how public sentiment influences the general direction of content pursued by reporters. Along with these structural implications, it would also be helpful to examine how the journalism industry’s foray into the field of social media doubles back to affect the industry and its actors.

What Gets Reported and How

First and foremost, social media immediately influences what we see and when we see it. Information easily outpaces even the most proficient journalist, and thus the industry has been forced to adapt to a system that would otherwise render professional journalists obsolete. The Arab Spring was only the latest in a line of social movements that exemplifies a simple idea: news can travel faster than anything else, even the newsgatherers. This significant increase in the speed of information exchange has made social media an invaluable- and perhaps the most valuable- form of news reporting.

The image above illustrates the point perfectly: Twitter waves can outrun seismic waves, and all of a sudden the citizens of Virginia get to learn about the earthquake they are to experience before they experience it. The reason for this is social media’s ability to harness the collective eye of an entire Internet population and direct its efforts at exposing the truth, at least to some degree. Although, as seen above, social media has long played a role in the organization of social movements, the mainstream media’s utilization of social media in this respect is new. Instead of fighting prevalent trends in citizen reporting, as seen with the use of Twitter to relayed real time information concerning the Arab Spring among followers and to the outside world.

Suddenly, an average Joe could serve as a CNN I-Reporter by sending in video of breaking news events to be broadcast on the 24-hour news network. But what did this mean for the substance of the content the media’s consumers would receive? This topic has cultivated much debate among the journalistic community, with supporters of citizen journalism indicating that a journalistic trend that allows readers more choice and transparency justifies the possible decline in journalistic quality encountered when professionals are no longer at the front of a breaking story. It is of little doubt that the people of Egypt would not have seen the sweeping changes they have recently encountered without the presence of large, engaged social media networks with users willing to convey real time information to the outside world. The fact that this information stream was partially cut off during the Arab Spring (below), presumably by some entity that felt threatened, further evidences the extreme influence social media can carry in the context of political movements.

The importance of Social media in the life cycle of the news is apparent from the very beginning- it not only redefines what content can possibly be available in real time, but it also allows citizen reporters to refocus our societal priorities by influencing what news is reported at all, and further influencing what gains traction in the traditional media. This cycle continues once the content reaches a professional, as reporters have had to adapt to the changing information landscape as well.

How this affects reporters

Journalists have only been able to survive with, and not in spite of, social media. The vast improvement in information relay speeds that comes with a large, socially engaged online network efficiently utilizes the disparate placement of its discrete members around the globe, thus acting as a virtual “global news net” that catches any story, no matter how good or bad. Herein lies the main argument against the so called “citizen journalist” trend (ie, a sever decline in journalistic quality). This is where professional journalists find their still existent, but possibly eroding, niche, one in which social media will surely play an increasingly important role in the near future, according to the BBC video below.

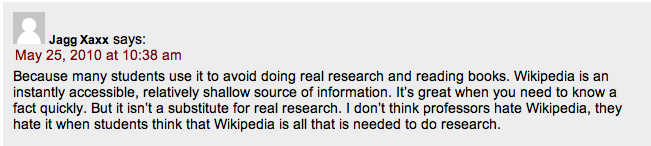

Obviously, this emergence of a new aspect of social media will catalyze changes within the journalism industry. First, there are the passive changes, or those that are a natural product of social media’s emergence onto the journalism scene (as opposed to an active effort by media companies to integrate social media campaigns, which I’ll talk about later). The primary changes are related to social media’s speed. If breaking news delivered so fast as to sacrifice quality of reporting is America’s drug, then social media is the enabler. To illustrate the whole “sacrifice of quality” bit, take the example of Amanda Knox, an American woman convicted of a murder allegedly committed during Knox’s study abroad period there. The Daily Mail waited anxiously to report the result of the woman’s murder appeal, and ran a headline proclaiming the announcement of Knox’s guilty verdict just minutes after the announcement. There was just one problem: Knox had been found innocent. The professional reporters got it wrong. In a rush to publish first that is then hyperized by a need to publish before the collective body of internet users can find information through social networks, professional journalists had royally mucked up a very basic reporting job.

In past journalistic generations, this phenomenon carried the popular phrase “never wrong for long,” referencing the 24 hour news cycle’s relative lack of need for accuracy, given that corrections to prior incorrect statements could be made at any time. The risk for committing errors was reduced, and thus a greater premium was placed on speed in reporting. Newsrooms have always moved fast. But social media is forcing them to move even faster, just to keep up with the flow of information over social networks. This increase in speed leaves little time for fact checking, and this often falls by the wayside completely when the relative penalty for a mistake is so small.

Or is the penalty so small? The flip side of the internet age coin with regard to journalism is that mistakes, though easily and quickly correctable, are also preserved on hard drives in web archives forever. Worse yet, the ferociously quick spread of information over social media can take on the personality of a wildfire, with sometimes devastating consequences. Consider the recent hacking of a Fox News Twitter account that led to false reports of President Obama’s assassination. The reports were eventually reported to be the product of vandalism and removed, but not before panic spread through the Twitter-verse. This type of hyper-speed response time, of which only internet-based social networks are capable, reflect simultaneously the greatest asset greatest detriment of social media from a journalistic perspective.

Next, one must examine the active changes in the activity of news organizations in response to developments in social media. Journalists, in their attempt to adapt to the ever-changing landscape of information technology, have in some cases used social media to actively bolster their own reporting activities. Social media has allowed journalism to transform into a dialogue between reporter and reader, and this relationship displays influence in both directions. When asked, reporters of all types indicated that social media had changed the way they interact with readers, thus evidencing social media’s growing importance within the journalism industry.

Since audience participation has now become a staple of online journalism, this relationship inevitable affects not only the reporting priorities of the journalist, but also the content covered. Reporters can now put a call out for information relating to a story and build breaking news coverage around a targeted audience that has proven its investment in the journalism provided by actively engaging it in an online setting. Reporters can use social media to direct their coverage and inform their stories, especially with platforms as extensive as Twitter which allows unlimited access to breaking news events through a vast, global user network.

Some networks and organizations have gone so far as to place social media campaign agendas at the center of their operating strategies, with Time magazine focusing solidly on amassing Twitter based followings for its various top magazines. The synthesis between traditional media modes utilizing new media and the participatory culture of new media lies in programs like CNN’s I-Report, which allows regular viewers to send the network breaking news stories with accompanying pictures and videos. This form of social media acts not only as a type of new wave marketing for CNN, but also as a means of news aggregation for use during the 24 hour news cycle. News gathering has been relegated as a task for the viewers, because their speed as harnessed by a network cannot be matched. The BBC has outlined similar goals for its social media utilization agenda, outlined in its video below.

Perhaps The Atlantic Magazine has embraced audience participation in the creation of media at the most fundamental level by opening its editing process to public comment. This outright endorsement of the effects of citizen journalism, at least during the editing process, signals an approval of the seminal effects this participation can have on the direction of news content. Users can now refocus the material on which news organization must concentrate their efforts, such as with citizen journalists in the Middle East. The journalists’ underscore this fundamental shift by acknowledging and apparently embracing new media, with sites such as MuckRack.com providing access to the story trends and ideas of reporters that allows user feedback which can help shape story angles and directions. In short, social media has had a dual effect on how reporters operate, both by reshaping the journalistic landscape and allowing reporters to tap into aspects of audience communication and participation that facilitate the growth of reader influence over journalism’s aims and targets.

Changing Answers Change the Questions

With the growth of social media as a method of amassing breaking news, discerning audience opinion and desires, and formulating story angles, the media has begun to change the types of questions it asks and the angle by which it attacks stories. Primarily, audiences are coming from different places (ie: social media outlets), which naturally affects the marketing strategies (and thus, the types of stories) pursued and pushed by traditional media sources.

With this change in traffic flow comes a change in how media must adapt to find audiences effectively. Integration with social networks is key, though this hyper-connectivity sometimes leads to undesirable instances of information communication. One BBC blog post asks the pivotal question: “What if younger readers start to see their friends as legitimate news sources?” It seems, for many circumstances, that this change has already occurred. This change in reporter-audience dynamic has proved so important as to cause the BBC to refocus its growth agenda with an emphasis on social media.

With all of these significant changes in how news gets reported, what garners attention as newsworthy, how audiences participate with reporters and how this participation shapes the image of modern media, one must ask if the news is better or worse of for the emergence of social media. It is obvious that journalists will have to continue to adapt to this changing landscape as social media becomes more prevalent. More importantly, it appears that the market for journalism no longer necessitates primary discovery of facts- this task has been given to amateur viewers who will provide the information for free through various social networking means. The task of the reporter in the age of social media will be to guide, to provide synthesis where there is only doubt and to shed light on the truth, not just “the facts.” It will also be the task of reporters to ensure that audiences are given fair treatment of what needs to be seen, not just what audiences indicate they wish to see via interactive media platforms. The danger with customized media through reader-reporter interaction is that the news will lose its primary purpose: to inform of the truth. If audiences are given to much sway over the angles and story ideas of future reports, the reports will begin to only resemble the prevailing modes of thought within the audience. It has always been the job of the reporter to challenge the status quo and to facilitate transparency as the best disinfectant. With the emergence of social media, our society waits to see if journalists are up to the task of reinventing themselves in order to face the hurdles inherent in the use of new media systems. Audience participation is here to stay, and this dynamic will obviously influence reporters to produce content tailored toward the engaged audience. This is our dilemma: what we want to hear may not always be what we need to hear. It will be the job of internet generation reporters to help us tell the difference.