Moglen: The Theory of Free Software

Eben Moglen lays out a grand vision for the incipient changes to the landscape of intellectual property. His paper concludes with little difficulty that free software as epitomized by the GNU/Linux model is both more efficient and less restrictive than the software dominion of Microsoft that characterizes the status quo. Moglen gives an historical argument for why free software is bound to succeed with his claim that “legal regimes based on sharp but unpredictable distinctions among similar objects are radically unstable.” As for the presently existing standards of the current legal regime, “Parties will use and abuse them freely until the mainstream of ‘respectable’ conservative opinion acknowledges their death, with uncertain results.” Intellectual property is bound to change, he prophesies. At the rhetorical summit of this vision, he even tells a New York Magazine reporter, “The people who have short-term needs for more money and more power are an ancient regime on the verge of being swept away.”

Moglen’s theoretical-historical understanding of current trends in intellectual property — and software ownership in particular — is on point. Things do need to change, and at a certain point they will change. But Moglen’s arguments leave open the question of how and when these changes will take place. Moglen offhandedly proposes the image of a “bellum servile of couch potatoes against media magnates.” Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that, but the image raises the question … is the notion of free software actually catching on? It’s clearly catching on with some geeks and law professors, but is it catching on with the public at large? In the lingo of Diaspora*’s consultancy firm: free software jives with the beards, but can it work for the girls?

Linux: The Bellwether for Free Software

Consider Linux. The open source operating system is the poster-child for the past, present, and future of the free software movement. Engineered in 1991 by Linus Torvalds, Linux has indeed made considerable inroads en route to its ultimate goal of world domination (or, toppling Microsoft). Most importantly, Linux currently powers over 60% of the world’s top 500 supercomputers, including the 10 fastest supercomputers in the world, a testament to its high-performance efficiency. Less importantly, but still indicative of increasing popularity, the government of Brazil has recently given Linux its official endorsement. “What interests the government is to give options, to give alternatives to the proprietary — to the almost monopolistic — domain,” said Brazil’s secretary general of science and technology in 2008. Other endorsements have come from the Russian military, the Chinese technology independence initiative, the Indian state of Kerala, and even the likes of France and Germany.

On the other hand, various sources estimate the desktop market share of Linux from less than 1% to 4.8%, while Microsoft maintains more than 85% of the market. According to Wikipedia, in terms of the usage share of web client operating systems, Linux sits at a minuscule 1.65%, in comparison with 81.97% for Windows OSs and 9.27% for Macs.

What will happen to Linux in the future? It has certainly grown by leaps and bounds over the past two decades, but while it has cornered the market for supercomputers and won the hearts of tech-savvy nerds around the world, it has yet to gain a strong hold on the general public in the United States. If and how Linux will overcome the Microsoft monopoly remain to be seen.

Diaspora*: The Viability of Baby Steps

But what about other “free software” efforts? Consider the makers of Diaspora*, who take Moglen as a primary source of inspiration. The Diaspora* crew see themselves as working towards Moglen’s grandiose vision of future digital communities — only, by a more immediate and pragmatic pathway. “[Moglen] sees way into the future,” says Max Salzberg, “We really like that conception, but there’s got to be a baby step.” The relevant baby step, says teammate Ilya Zhitomirskiy, is that “we want to move people from websites that are not healthy, to websites that are more healthy, because they’re transparent.” In particular, the makers of Diaspora* want to move traffic away from the perennial privacy villains Facebook, and onto their own, open, decentralized social network.

Is Diaspora* a viable project? Can it compete with Facebook for social networkers around the world? Needless to say, Facebook possesses one advantage that may prove to be insurmountable: the enormous inertia of its 600 million current users. Diaspora* will have a tough time recruiting Facebook users when they must abandon their present abode, leaving behind them the critical mass of friends and contacts already registered on Facebook.

Diaspora* can, however, offer a number of things that Facebook cannot. Share what you want, with whom you want, says its homepage, in stark contrast to Facebook’s offer to give you: “spying — for free!” Specifically, Diaspora* claims that it offers three innovations to the social network model: (1) choice, by which users can sort their contacts and share particular information with the precise audience of their choice; (2) ownership, by which users can maintain their claims to anything posted on the site; and (3) simplicity; by which privacy options are straightforward and transparent to users at every point. All three are significant improvements on Facebook.

Diaspora* certainly delivers on these promises — just set up an account and see for yourself — and what’s more, it even makes the effort to smooth users’ transitions from their Facebook accounts. For instance, while you can’t friend someone on Facebook via Diaspora*, you can now post Facebook status updates via your Diaspora* account.

So will Diaspora* succeed, over the next few years, in wooing the Facebooking masses? It’s certainly possible, especially when people start to realize that Facebook (a) isn’t all that special, and (b) isn’t all that great with its users’ privacy. As Moglen points out, Facebook’s promise essentially amounts to, “I will give you free web hosting and some PHP doodads and you get spying, for free, all the time.” This is not a very attractive offer, when stated in such stark terms. As Diaspora* collaborator Rafi Sofaer puts the thought, “We don’t need to hand our messages to a hub. What Facebook gives you as a user isn’t all that hard to do. All the little games, the little walls, the little chat, aren’t really rare things. The technology already exists.”

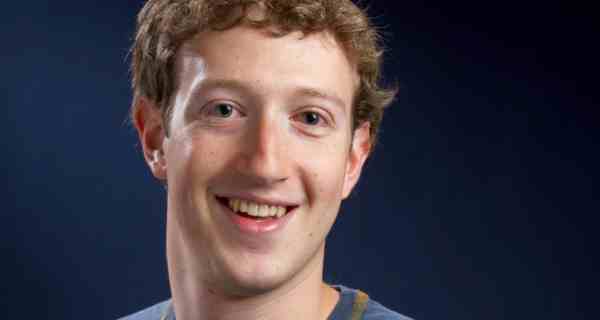

Whether Diaspora* flourishes or crumbles over the next two years remains to be seen. But at the very least, the young networking site has one deep-pocketed friend: Mark Zuckerberg himself. “I think it is a cool idea,” said Zuckerberg, who donated an undisclosed amount to the project. He admires the group, he says, in part because he sees “a little of myself in them.” Whether his donation was a gesture of condescension, a public relations gambit, or a genuine statement of support will remain a mystery, but the thought of Diaspora* as a new-and-improved Facebook in the making is certainly an exciting one.

Having used Yale library for the past four years, I’ve come to accept as fact that the wonderful invention of the e-Book allows all library users to bypass the logistical obstacles that accompany the borrowing of physical books – unavailability when checked out by others, the trip of physically finding and retrieving the title from its shelf, the revulsion of thumbing through dilapidated volumes with unidentifiable stains. More than once, I’ve taken Yale classes in which professors have assigned books that are available online from the Yale library. The strategy for those readings has always been to click on the link whenever I want, at my own pace and timing. The only “hassles” were perhaps that the pages cannot be printed, and that some versions do not allow electronic markings or highlights. Small price to pay for the convenience offered.

Having used Yale library for the past four years, I’ve come to accept as fact that the wonderful invention of the e-Book allows all library users to bypass the logistical obstacles that accompany the borrowing of physical books – unavailability when checked out by others, the trip of physically finding and retrieving the title from its shelf, the revulsion of thumbing through dilapidated volumes with unidentifiable stains. More than once, I’ve taken Yale classes in which professors have assigned books that are available online from the Yale library. The strategy for those readings has always been to click on the link whenever I want, at my own pace and timing. The only “hassles” were perhaps that the pages cannot be printed, and that some versions do not allow electronic markings or highlights. Small price to pay for the convenience offered.