“There may never be another you,” notes the website of the DNAid art project, “but if there ever should be, would you have any legal rights to the original design?” The answer seems like it should be simple enough: of course we own the rights to our own DNA- it’s a part of ourselves that helps fundamentally define who we are. And even if we didn’t necessarily own the rights to our personal genetic code, it’s not like anyone else could.

Experimental artist Larry Miller, however, disagrees. Miller was alarmed by the emergence of genetic patents following the Supreme Court’s 1980 decision in Diamond v. Chakrabartry, which held that living beings and their DNA could be patented under U.S. law; he worried that as genetic technology became more and more prevalent, our rights over the code which makes us us would erode. As a response in 1989, Miller became the first person on record to copyright his own DNA.

He was now a Certified Original Human- a man whose genome was no one’s but his own.

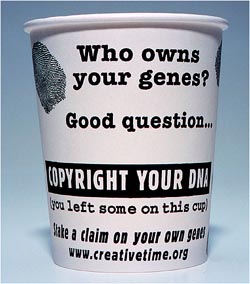

Miller wasn’t content to stop with just protecting his own genes- several years later he made the “Genetic Copyright Certificate” and encouraged others to assert their ownership over their DNA. He sought to generate dialogue over the expanding role that genetic engineering was playing in a society where GMOs were doing everything from feeding us to curing disease. His genomic rights evangelism expanded as thousands “copyrighted” their genes and word spread via the internet, news media and even, for a time, coffee cups (which is all well and good until Starbucks decides the next logical step in expansion is to do to your DNA what they’ve done to every street corner in NYC).

The work of genetic artists like Larry Miller certainly raises questions, but does it offer us any answers? The copyrights he helped create have never been legally tested, but would they hold up if they were? The Register of Copyrights explains that “copyright exists from the moment the work is created,” but does that mean we’ve always owned our genes and Miller was just the first to point that out?

Further, supposing that these were enforcible, how would that happen? If someone creates a genetic copy of us (or any other derivative work based on our genome), can they claim fair use? Can we send a cease-and-desist letter (and what would it mean for an organism to “cease and desist” using another’s genes)? Can we ask them for royalty checks?

These are confusing questions, to be sure, but that’s Miller’s whole idea. He wants to make us ask the awkward and unclear questions about where genetic intellectual property is leading us. He wants us to be confused. He wants us to be concerned.

Even the moniker offered by DNAid, “Certified Original Human,” ends up offering more questions than it answers. If our genes are derived from our parents, can any of us be considered “original?” Even if we can, why should we claim copyright over our DNA if we didn’t create it? After all, it’s our genes that make us- not the other way around.

At least, not yet.

larger ratio of the overall Thai patent application pool than either of the two leading nations. These patents have been in a wide variety of biotech fields but two of the most striking are agricultural biotech patents, and, of course, drug patents. On the agricultural side, the now great success has been with their genetically modified resistant rice. This helped the Thai agricultural economy expand rapidly and has made Thailand the largest exporter of rice in the world. Beyond this, Thailand is one of only five nations in the world with net food exports. This transformation into an agricultural powerhouse has had a ripple effect by also increasing employment rapidly and consuming land in the nation so that today, over 50% of the arable land in Thailand is used for rice production.

larger ratio of the overall Thai patent application pool than either of the two leading nations. These patents have been in a wide variety of biotech fields but two of the most striking are agricultural biotech patents, and, of course, drug patents. On the agricultural side, the now great success has been with their genetically modified resistant rice. This helped the Thai agricultural economy expand rapidly and has made Thailand the largest exporter of rice in the world. Beyond this, Thailand is one of only five nations in the world with net food exports. This transformation into an agricultural powerhouse has had a ripple effect by also increasing employment rapidly and consuming land in the nation so that today, over 50% of the arable land in Thailand is used for rice production.

Indeed, the beauty of having a patent on life forms is that you cannot curb scientific innovation that scientists control themselves; heterozygote oncomice who mate have progency that are 75% oncomice.

Indeed, the beauty of having a patent on life forms is that you cannot curb scientific innovation that scientists control themselves; heterozygote oncomice who mate have progency that are 75% oncomice.